A question for all mayoral candidates: what if our city’s stunted growth has less to do with the people in charge of our city? What if the true issue is with our overall philosophy on economic development?

There’s so much to love about Louisville.

Me, I love the way the sunset looks between the trees in Clifton. In my mid-20s I’d watch the light fall between the leafy vines twisting along the pergola outside of Heine Brothers (formerly Vint) on Frankfort Avenue and feel an aching warmth for my hometown. I loved too how the summertime trails snaking near Big Rock provide just enough privacy and romance that no Highlands courtship is complete without an excited kiss there above the water. As a kid, I loved the 4th of July in Tom Sawyer Park, the whole earth shaking with fireflies. That show eclipsed only by the way the heavens seemed to burn on the reflective face of the Ohio River during Thunder Over Louisville.

I’ve fond memories of Derby in Shively where cars were haphazardly parked, partially blocking the street, as family chased the smell of barbeque and shouted the names of $2 horses drawn from a hat. Memories too of the little house my family bought my grandmother in Park Duvalle that smelled like cigarette smoke and tasted like dill pickles. She would give me and my sisters pickles as she told loud, exaggerated gossip about her neighbors and lavished praise on her pastor at Cable Baptist Church.

As an adult, I love long bike rides past the shaded mansions on either side of Southern Parkway and the skyline view from the Iroquois Park overlook. I love that view almost as much as I love Jack Taps at ShopBar and arguing about politics with my partner and her best friend over loud, live music at Z-Bar. The best friend loved to stay out until 4 am when the bars closed and I, a morning person, did not love that so much. Still, I love that this city gives us the option to form so many fun late-night memories. I do love this city.

I love it, and I acknowledge that it is bleeding.

We’re almost two years now since Breonna Taylor was killed in her own home, David McAtee defending his restaurant from the National Guard, and since our city streets buckled under the weight of massive demonstrations. Since then, we’ve seen another record year for homicides. We’ve also seen our police gain better pay as they patrol the same neighborhoods where one year ago so many were calling for the city to defund them. A recent working paper found that Louisville was among the three worst cities in the U.S. in terms of housing discrimination against Black and Hispanic renters. Our business community continues to bemoan the loss of activity downtown (which is also due to COVID shutdowns), and blame the Mayor for not doing enough to satisfy existing large employers like Papa Johns which moved its headquarters to Atlanta. We’re now walking into the new year with little that I would call justice on the racial discrimination front behind us, and with no bold economic plan being sold to the public that would both grow our city and move us closer toward equity in the years to come.

But it’s not too late for us to move on equity. Two years into a deadly pandemic, racial reckoning, and j-curved recession, Louisville is uniquely positioned to grow stronger from its nightmare experiences and become more the place that is worthy of our love. In 2022, we will elect a new mayor, the first change in administration in over a decade, and that new administration will have the opportunity to learn from the many inequities that the last few years have laid bare.

To bring Louisville from the ashes and pave the way toward a more equitable future for all people from Shawnee to Lake Forest, we need our next mayor to be bold enough to walk into their economic development office and ask one critical question: who benefits from our work?

Dubious Assumptions Behind Municipal Economic Development Strategies

The problem with municipal economic development strategies, as I see it, has a lot to do with Democratic leaders in urban areas holding tight to a politically conservative conception of economic development. Leaders of the Democratic Party find themselves at odds with two parts of their identity: the socially progressive desire for equity and inclusion, and the socially regressive idea that increased capital and free-market forces are the best way to develop a city.

The increased capital and free-market forces argument for economic development is often armed with the age-old myth that a rising tide of capital will lift all boats. Elected officials in cities across America have been retelling this same tale for decades and it has justified exploitative and extractive municipal systems. Systems that have resulted in the extreme inequality that has weathered the patience of the American people and is currently threatening to rip the fabric of our country.

I want to challenge the “rising tide” assumption propping up today’s most popular municipal economic strategies. The “rising tide” assumption posits that by poaching new businesses from other municipalities we can grow tax revenues for our city and increase the wages of our city’s residents. I don’t doubt that new businesses lead to increased tax revenues. I do, however, seriously doubt that a strategy focused on bringing new businesses to the Louisville workforce would do much to raise wages for the people who are already here – especially our low-wage workers that have historically been blocked from wealth-generating opportunities.

To put it more plainly, I don’t believe that a rising tide of capital in cities lifts all boats.

The Rise of Inequality in Other Cities

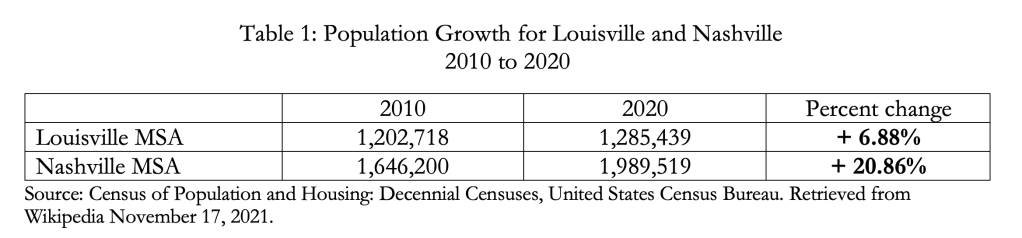

Evidence for the “rising tide” approach’s failure to prioritize equity can be found in our peer cities. Nashville is often looked at as a shining, if not nuanced, example of a Southern city that boomed economically over the last decade so I will use them as my primary example. Looking at Nashville, we can see the impact of growth in an urban metropolitan area on the poorest and richest among us. In the time between the 2010 and 2020 Census, Nashville’s population grew by 20.86%. In that same period, Louisville’s population grew by 6.88% (Table 1).

One of the theories of the “rising tide” strategy is that cities, and the people in them, benefit from more population growth spurred by the acquisition of new businesses while shrinking cities lose revenue, lose employers, and become economically insecure over time. To examine this theory, I gathered wage data for both cities.

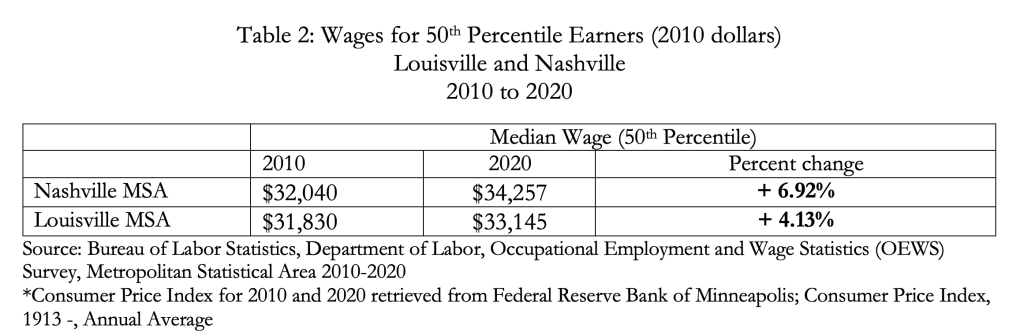

When we look at how wages have evolved in Nashville and Louisville over the past decade, we see that the median wage did increase more in Nashville than in Louisville. However, the relative difference in wage increases is much smaller than the relative difference in population increases (Tables 1 and 2). This suggests that growth may not be a great predictor of median wage increases in these cities.

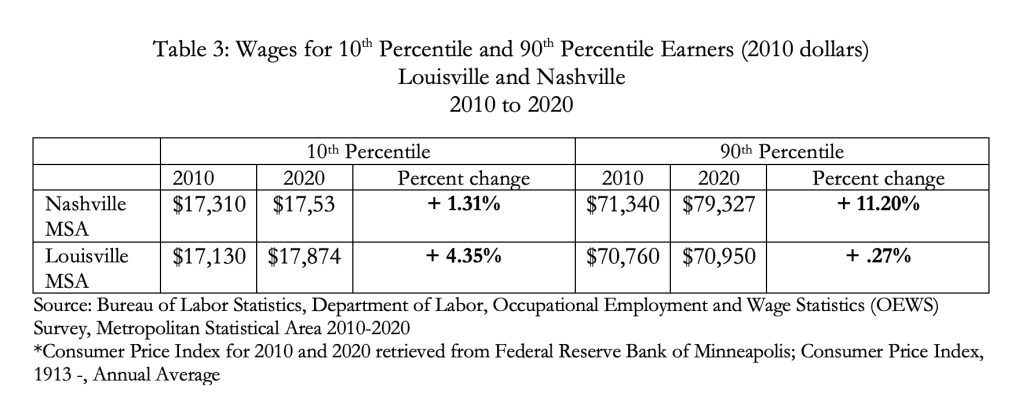

Additionally, the wage increases that Nashville did see weren’t felt evenly across wage levels as the “lift all boats” approach to economic development promises. When we look at Nashville’s wage distribution changes over the past decade, we see almost no wage growth at the bottom compared to the top. In fact, Louisville’s lowest wage earners earned a larger wage increase during the same period despite our city experiencing less growth (Table 3).

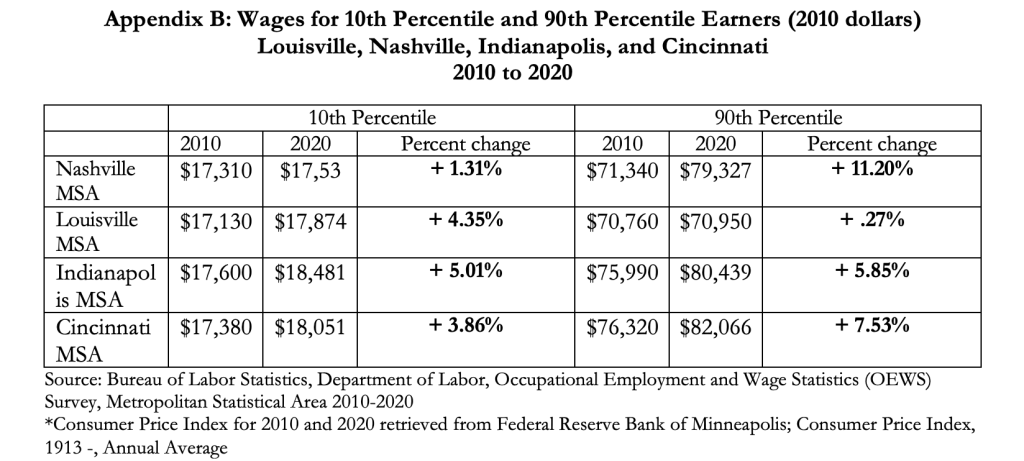

This isn’t only true for Nashville. I looked at real wages for two other peer cities – Indianapolis and Cincinnati – experiencing more modest growth over the past decade. Only Indianapolis saw a percent increase in real wages for lower 10th percentile earners that was close to the percent increase in real wages for the upper 90th. Still, in Indianapolis, just as in Nashville, economic growth did not bring the two poles of the wage-earning distribution closer together. The city only came closer to maintaining the same wage gap (Appendix B).

So, when we ask, “who benefits,” economic development strategies employed by our comparison cities like Nashville, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis, at worst, tend to largely benefit individuals making the highest wages while low wage earners see little increase in their overall purchasing power. At best, the strategy increases earnings at all wage levels but maintains the same degree of wage inequality. Public money should not prioritize the increase in wealth of the wealthiest members of society, nor should it stop at maintaining the previous decade’s wage gaps. Public money should be used to make the playing field as equitable as possible, which means that it should prioritize lower-wage residents.

Ideas for Why the “Rising Tide” Strategy Doesn’t Work

So, why doesn’t the strategy work?

Wages

Consider this: a tech company decides to locate in Louisville and brings with it 100 jobs. It is plausible that some of these jobs will be filled by employees currently with the company from another state (either relocating or working remotely). The remaining jobs get picked up by people in Louisville’s tech-educated workforce; a small population in Louisville that I would assume mostly consists of young people from comfortable backgrounds.1 These are the only workers in Louisville who would see immediate wage increases.

Economic development proposals commonly assume that new high-wage jobs benefit more than just the employees who get them because higher wages for some lead to increased spending in the local economy overall. The assumption is that new high-wage employees spend more on local services (restaurants, housekeepers, dog walkers, dry cleaners, barbers, etc.) and that this increased spending leads to increased wages for the lower wage employees who provide these local services.

More likely, the employers of these service economy jobs would keep their profits. Power imbalances between owners and workers in the service sector make it so that increased profits would lead to wage increases only when the market is in such a state that employers are forced to compete over labor. Only recently have we seen a spike in pay for service economy workers across the nation, and it wasn’t due to increased service sector profits in our cities; it was due to the COVID-19 pandemic giving employees a reason to quit in droves or go on strike, making them more valuable and giving them greater bargaining power.

Without the present labor shortage and increase in employee bargaining power, local businesses would not increase wages. David Card and the late Alan Kruger shared the 2021 Nobel Prize in economics in part for the empirical evidence they found challenging this naive economic concept, also known as competitive equilibrium. Competitive equilibrium assumes that the market is competitive, and prices are freely determined. In that state, profit-maximizing producers and utility-maximizing consumers arrive at a price that allows the supply of a good to meet the demand. Their 1993 study of minimum wage increases for fast food workers observed changes in employment in New Jersey, which raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05 per hour, and changes right across the river in Pennsylvania where the minimum wage remained at $4.25.

Conventional economic theory suggests that profit-maximizing employers in New Jersey would have to cut jobs in response to the sudden increase in labor costs. Card and Kruger found that the opposite occurred. The minimum wage increase led to no decrease in employment in New Jersey. Instead, it led to a 13% increase in employment, relative to stores in Pennsylvania. The result verifies that profit-maximizing employers could pay their employees more without shrinking their workforce. This is because the market for labor, a market in which employers usually have more power over costs than employees, isn’t all that competitive. The lesson: it is naive to assume that employers will pass profits down to employees in the form of higher wages in a non-competitive labor market. An increase in consumer spending in Louisville neighborhoods would not necessarily lift the boats of other wage earners working in those same neighborhoods.

Housing and Sense of Place

Even if more spending from high-wage earners led to a modest increase in pay for middle- and low-wage earners, the increased presence of high-wage earners in a neighborhood can have negative impacts on the people already living there. Outsiders with money can cause the city’s housing/renting costs to increase and may increase the cost of goods in the neighborhoods where these high-wage earners locate. The wage increases of Louisville’s average worker, if they occur, would likely fail to keep up with rising costs.

I will admit that I am also making an assumption when I claim that increasing the number of higher-wage earners would lead to the undesirable effect of increased housing and renting costs in parts of our city. One could imagine a scenario where, as new jobs come in, new higher density housing gets constructed (maybe even with some units designated as affordable housing). Displacement could then be minimized by allowing new housing to replace industrial properties such as warehouses, factories, and vacant lots. While possible, the reality is often very different due to local politics and a concept known as Not In My Backyard or NIMBYism.

When vacant land is available for high-density housing in middle-wage and high-wage neighborhoods, local politics make development all but impossible. There’s a stigma to apartments that sometimes inspires backlash from current residents when they are proposed nearby.2 It is much easier to build new housing, and especially high-density housing, in less wealthy, less white areas. So, let’s say these new tech workers do move here, and that other industry professionals move here to be near an emerging market – they will need places to live. Additional housing to meet the increased demand would be most likely slated for areas such as Smoketown, Shelby Park, and California, instead of the Highlands, Prospect, or St. Matthews. Or, if single-family housing is desired near the city center but on affordable land, developers may consider building or flipping homes in the West End.

Developing in Louisville’s West End would raise the property value and property taxes on current homeowners. In either case, low-wage Louisvillians could find their homes too pricey to keep until a point where the same taxpayers that financed this campaign to bring more capital to Louisville, might need to sell their homes because of the very same campaign’s success. Selling a home for profit isn’t inherently bad. But this avenue of wealth generation for low-wage earners is less appealing when it means that you ultimately must leave your neighborhood, either because of increased property taxes or because the changing character of the neighborhood means you feel like you no longer belong there.

This is the gentrification scenario that haunts every 21st-century economic development office. In this scenario, Louisville increases its tax base by taxing the new company and from poaching higher wage employees, but very few original Louisvillians get anything out of the deal. If you are poor, this rising tide will not lift your boat; it will ask you to sell your home, push you further out into the exurbs where social services and public transit are insufficient and prepare no answer for you when you become more isolated once that happens.

Who benefits? If the goal of the public sector is to make some upper-middle-class families in Louisville better off while pushing low-wage families further out into the county, then chasing outside capital to grow a city is a good strategy. I don’t think this outcome is what most Democrats want. Nevertheless, it is the reality that such economic development strategies often produce.

A Better Purpose for Economic Development Offices

Louisville is not a place for me; it is a home. In this home, there are people and places that matter in ways that public policy and economic strategy often fail to account for. It’s the parks and parties, the neighborhoods and neighbors, the fireworks and first times. It’s where the lady who gave me dill pickles was laid to rest and where the friend who loved 4-ams ashes are spread. It’s where I was born and likely where I’ll die too, and I need it to improve before I do that. Improvement requires that policy and economic strategy, not the free market, makes an honest account of the value in all of us residing here.

The philosophy that the market can solve everything has not held true and should not be adopted by our public sector leaders. The idea that the job of the mayor is to make sure that cities generate as much money as possible is an idea that will only lead to greater inequities, more public frustration, and the further crumbling of cities in the decades to come.

We need our next administration to offer an economic strategy that capitalizes on the talent of current Louisvillians. I would like to see an organized and aggressive economic movement in Louisville that prioritizes the city’s race, safety, and belonging issues over recruiting outside capital.

How powerful it would be to declare that Louisville is the nation’s first anti-poverty city; a place where poverty might still exist, but where the full weight of the economic development office, the business community, religious community, nonprofit sector, and higher education system are dedicated to the cause of ensuring every resident’s basic needs are met. What if the people of Louisville felt they could advance themselves here, build businesses here, take creative risks here?

Human potential is the most valuable asset in any city. Smart people trying the same failed strategies won’t unlock this potential. What might unlock it is a new strategy: if leaders have the courage and patience to try something different. What just might unlock Louisville’s human potential is a strategy that directly invests in the humans of Louisville.

By understanding our city’s people and their needs, then investing directly in them, we can build a community where previously untapped genius can flourish; one so thriving in realized human potential that other people and businesses will want to come here too. Louisville could be on track to be much more than a compassionate city; it could be the nation’s first equitable one. No other economic development strategy is honestly trying to accomplish that goal. Let’s be the first.

- The Fischer administration is working on this problem for the tech example that I’ve chosen. In 2021, Microsoft added Louisville to its Accelerate initiative, which is designed to provide digital skills training and professional development to individuals from traditionally underserved communities. In 2019, Metro Government launched LouTechWorks to facilitate a coordinated campaign across the city’s K-12, higher education, non-profit, and private sectors to broaden the city’s pool of employable tech workers. In 2015, KentuckianaWorks launched Code Louisville, a program that provides free instruction in web and software development, data analytics, user experience design, and more to help adults start a career in the tech industry. In the future, the backgrounds of people getting hired to work in the tech industry in Louisville might be more diverse.

- A recent example can be found in Prospect, where the low-wage, high-density project “Prospect Grove” was proposed in a suburb of Metro Louisville that is overwhelmingly white, high wage, and mostly defined by single-family homes. In 2017, Prospect mounted such an aggressive campaign against the project that Metro Council voted to block the zoning change that would have allowed the project to move forward on the currently vacant plot. In 2020, a judge upheld that decision. The One Park development slated on a vacant lot near the wealthy and predominately white Highlands neighborhood serves as another example. One Park was eventually approved, but only after two years of debate and 11 public meetings, a process that would have exhausted most developers.

- I want to give a huge thank-you to Michael Fryar, who introduced me to the Card and Kruger study on competitive equilibrium and whose conversations with me on naïve economic theories informed a lot of what ended up in the Ideas for Why the “Rising Tide” Strategy Doesn’t Work section of this essay.

- A shoutout to Lena Muldoon as well, for constructively pushing back against my critiques and informing me of the work Metro government is doing to address the issues I write about. I’m grateful too for her willingness to debate tough questions with me and demand we all do more to find equitable solutions to our city’s problems.

- And a final shoutout to Amy Clay for putting up with my conversations on this topic since I became obsessed with it in October 2021. Thanks for the many conversations that helped tease these thoughts out, for encouraging me to keep writing, and for your careful editing eye.

- Image of houses used at the top of this essay are from http://www.clipart-library.com

Note: the views and opinions expressed on PolitiFro are my own and do not necessarily reflect the position or views of my employer or any entity with which I am associated. Welcome to my mind and beware: it changes.

Like something you’ve read here? Sponsor the early morning coffees or late night beer that help make this blog possible. This is in no way necessary, but will make me feel good! Donate $5, $10, or any amount on Venmo: @Dexter-Horne or through CashApp: $DexterHorne. And as always, thanks for reading.